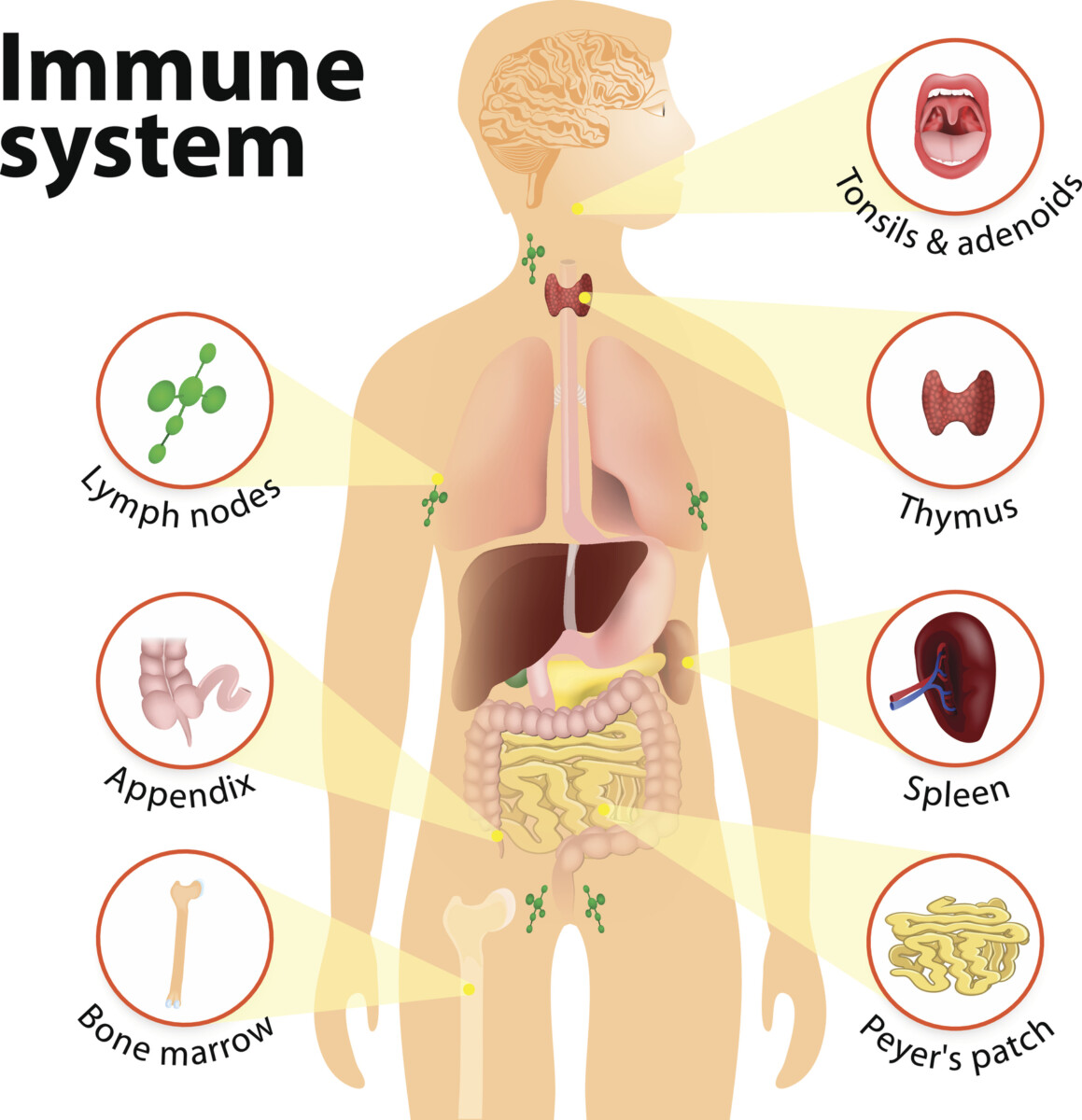

The immune system is complex and needs to protect the body from viruses, bacteria, fungi, tumors, and tissue damage among other things. The primary immune organs in the body are the thymus and the bone marrow in the long bones of the extremities, ribs, and cranial bones. Secondary immune organs are the spleen, lymph nodes, and lymphoid tissue – such as the tonsils – that is located at the multiple ports of entry into the body.

To function appropriately, the immune system needs to be told when something dangerous has entered or is occurring in the body. This information is provided by good lymphatic flow so that any foreign substances found in the fluid surrounding the cells are transported to lymphoid tissue, lymph nodes, and spleen where immune cells are activated to enter the fight.

The immune system can be divided into 2 primary systems that act synergistically: innate immunity and adaptive immunity. The innate immune response is the 1st line of defense that acts in minutes to hours after an area of the body is exposed to something harmful. Its response is general and non-specific. The adaptive immune response begins days to weeks later after being triggered by innate immune cells. The adaptive immune system then creates a more specific response by generating B cells and T cells.

B cells produce antibodies that attach to the specific foreign substances and make them inactive. T cells destroy the specific foreign substances present. Both B and T cells form memory cells that remain after the immune response ends, which results in a quicker and more specific response if the same antigen re-appears later.

Both B cells and T cells develop from progenitor cells in the bone marrow. Once created, mature B cells are released from the bone marrow into the body. However, before T cells are released, they must first travel to the thymus (T is for thymus) that sits in the chest directly behind the sternum. In the thymus, T cells are taught what foreign invaders to attack and to avoid the body’s own cells to prevent an autoimmune reaction.

After they are created, B and T cells leave the bone marrow and thymus and travel throughout the body to populate the various lymphoid tissues. So, for good immune function, even in adulthood, manual therapy can be quite helpful. The goals are:

1. Maximize lymphatic drainage by removing dysfunctions in the thoracic inlet (clavicles, upper ribs, and lower neck) where the lymphatic system drains and in the respiratory diaphragm, pelvic floor, and cranium that serve as lymphatic pumps. Enhance lymphatic flow even more by encouraging exercise and body motion as they wring the tissues and move lymph forward.

2. Remove dysfunctions present in the long bones of the extremities, ribs, and cranium where the bone marrow produces immune cells.

3. Remove dysfunctions in the sternomanubrial region (manubrium, sternum, and 2nd rib) to optimize thymic function.

Stay well!

Additional suggested reading:

Kooshesh, KA, et al. Health Consequences of Thymus Removal in Adults. N Engl J Med. 2023; 389:406-17. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2302892

Thorac Surg Clin. 2019; 29(2):123–131. doi:10.1016/j.thorsurg.2018.12.001.